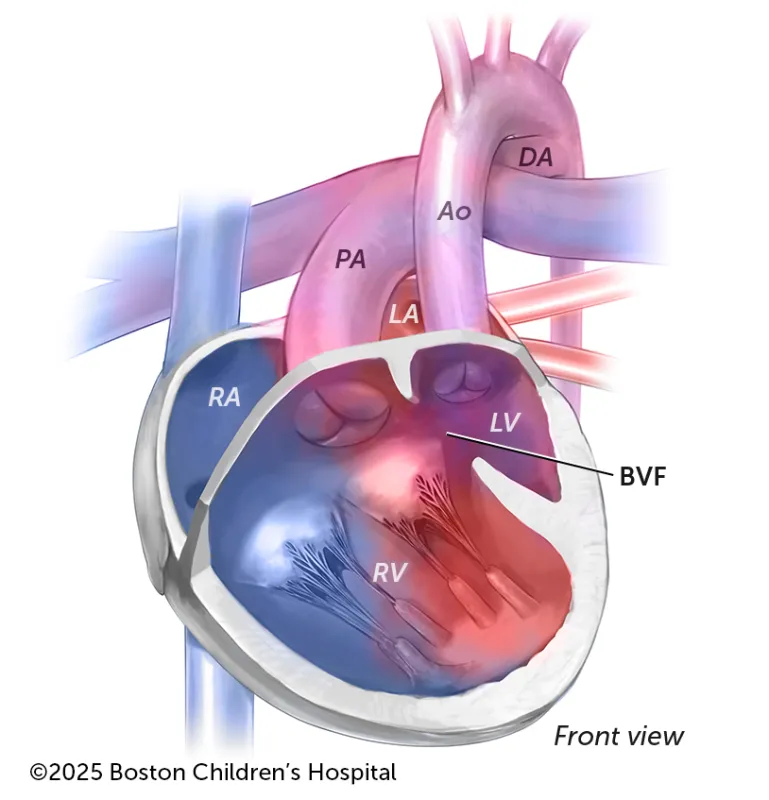

When the aorta comes from the left ventricle and the pulmonary artery comes from the BVF, your child may not need treatment immediately after birth.

Breadcrumb

What is double inlet ventricle (DIV)?

Double inlet ventricle (DIV) is a rare congenital heart defect (CHD) that changes the anatomy of the heart’s four chambers and affects circulation. Instead of having two working ventricles, a child with DIV has only one working ventricle. Depending on how DIV develops in a child, it may require treatment immediately after birth. That’s why it’s important for a newborn who hasn’t been diagnosed prenatally but has symptoms of one of the two types of DIV — double inlet left ventricle or double inlet right ventricle — and hasn’t been diagnosed prenatally to promptly have their circulation and heart assessed.

DIV can be treated through cardiac catheterization and cardiac surgery. The most common surgical treatment strategy is single ventricle palliation, which gives children a Fontan, or single ventricle, circulation. Children who rely on a single-ventricle heart can receive lifetime support. An alternative surgical treatment option that was pioneered by Boston Children’s, ventricular septation, can benefit some children who rely on their left ventricle.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of double inlet ventricle?

Typically, the left atrium is connected to the left ventricle, while the right atrium is connected to the right ventricle. With DIV, both atria are connected to the one working ventricle.

If the left ventricle is the only working ventricle, the name for that type of DIV is double inlet left ventricle (DILV). If the only working ventricle is the right ventricle, it is called double inlet right ventricle (DIRV).

Because the one working ventricle pumps blood from both atria, a mix of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood circulates into the lungs and body. This may cause a child to have difficulty breathing from a shortage of oxygen. If a child has DIV and transposition of the great arteries (TGA), their health is at greater risk after birth.

Other symptoms of DIV include:

- Blue or purplish color of the skin, lips, and the beds of fingernails and toenails (cyanosis)

- Fatigue and tiring easily

- Trouble feeding and gaining weight

- Excessive sweating

- A heart murmur

- A fast or irregular heartbeat

- A buildup of fluid that causes swelling in the abdomen and legs (edema)

What causes double inlet ventricle?

Children are born with DIV. It is believed to happen early in pregnancy, when the heart is developing, but the exact cause is unknown.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is double inlet ventricle diagnosed?

A routine prenatal ultrasound during pregnancy may detect DIV, prompting a secondary test, a fetal echocardiogram. If your child shows symptoms of DIV after birth, a cardiologist will first listen to their heart and lungs and measure their oxygen level. This exam can give your cardiologist an idea of the condition.

The cardiologist may also request an:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

- Echocardiogram (cardiac ultrasound)

- Chest X-ray

- Cardiac catheterization

What does it mean if your child is diagnosed with double inlet left ventricle?

If your child has DILV, one of their two “great” arteries (either the pulmonary artery or the aorta) has to connect to the left ventricle through a side chamber of the heart called the bulboventricular foramen (BVF). How urgently they will need care depends on which of the two arteries uses the BVF for that connection.

- When the aorta comes from the left ventricle and the pulmonary artery comes from the BVF, your child shouldn’t need treatment immediately after birth.

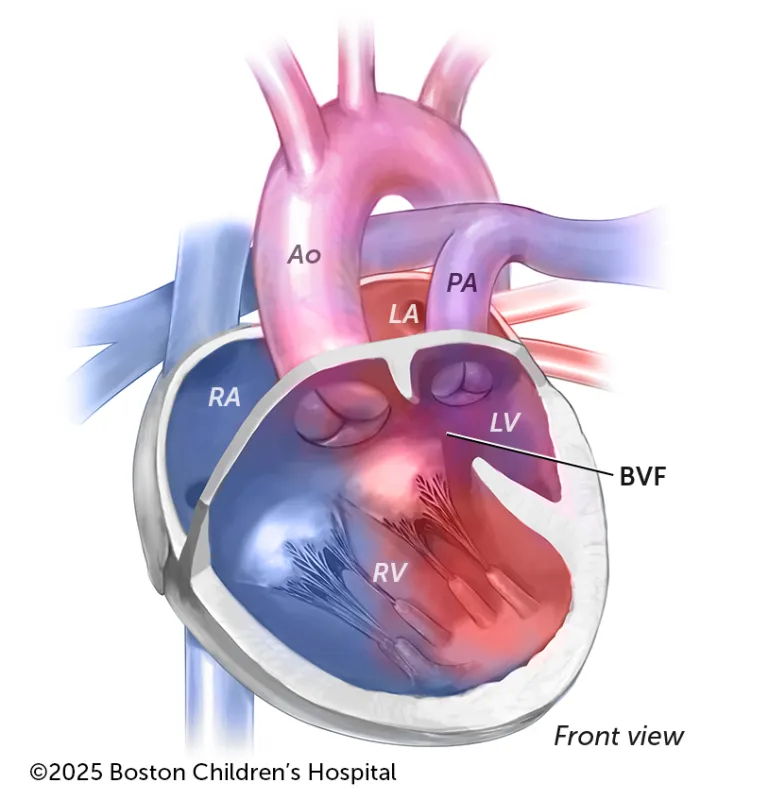

- When the aorta comes from the BVF that means your child’s arteries are switched (the condition TGA). They could also have coarctation of the aorta (a narrowed aorta). If your child has these conditions, their circulation is not optimal. They may need to have surgery almost immediately after birth.

When the aorta is on the right side of the heart, in this instance coming from the BVF, and the pulmonary artery is on the left side that means your child’s arteries are switched (the condition TGA) and their circulation is not optimal. They may need to have surgery almost immediately after birth.

Key:

- DA: Descending aorta

- AO: Aorta

- PA: Pulmonary artery

- RA: Right atrium

- LA: Left atrium

- RV: Right ventricle

- LV: Left ventricle

- BVF: Bulboventricular foramen

Which heart conditions are associated with double inlet ventricle?

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD), a hole in the heart wall that separates the ventricles

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Pulmonary atresia, when the pulmonary valve doesn’t develop properly

- Pulmonary valve stenosis, a narrowing in the opening of the pulmonary valve

- Leakage of the atrioventricular valves

- Poor contraction of the heart muscle

How is double inlet ventricle treated?

Almost all children who have DIV need surgical treatment. The timing depends on the severity. Some newborns can wait a few months. Others need treatment immediately after birth because they are at risk. Here are treatment options our Department of Cardiac Surgery will consider for those children:

Immediate treatment options for some newborns

- If your child has too little blood flow reaching their lungs, their blood-oxygen saturations can be monitored carefully. But if your child has extreme cyanosis or hypoxia (oxygen deficiency), they may need either a stent or shunt to improve blood flow.

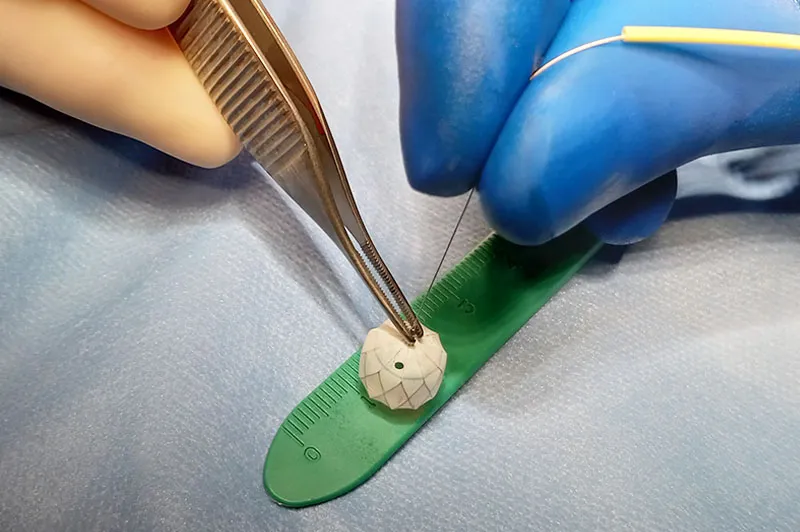

- If there is too much blood flow going to their lungs, they may need either a pulmonary band or pulmonary flow restrictor to lessen blood flow.

- If your child has TGA, coarctation of the aorta, or hypoplastic aortic arch along with DILV, there are several surgical options that depend on the BVF. They can have aortic arch reconstruction and pulmonary arterial banding if the BVF can support circulation. If the BVF cannot support circulation, they can have either an “arterial switch” operation or a procedure known as Damus-Kaye-Stansel (DKS).

- If your child’s circulation is stable, specialists from our Single Ventricle Program will monitor your child until they are ready for surgery.

Read how pulmonary artery flow restrictors are a “gamechanger” for treating newborns with overcirculation.

Treatment options for all children with DIV

Whether they had emergency treatment after birth or were able to wait a few months, almost all children who have DIV eventually will follow one of two treatment pathways:

Biventricular pathway

Specialists from our Complex Biventricular Repair Program will examine your child’s heart to determine if it can function with a ventricle that would be divided into two sides (a septated ventricle).

If your child is a candidate, they would have two surgeries known as staged ventricular septation. The first stage will typically happen when your child is 4 to 6 months old. The one functioning ventricle is divided. More ventricular septation surgical repair and the treatment of the VSD happens in the second stage, typically when your child is 2 or 3 years old.

Single ventricle pathway

If ventricular septation is not an option, your child can have two surgeries that change the flow of blood so that the one ventricle can better support circulation:

- Bi-directional Glenn procedure: Performed when your child is between 4 and 12 months old, the procedure replaces the shunt (which their heart will outgrow) with another connection to the pulmonary artery.

- Fontan procedure: Usually performed in the first few years of life, the Fontan directly connects returning blood from the lower body into the pulmonary arteries, bypassing the heart.

Children who had a bi-directional Glenn but who are eventually not ideal candidates for the Fontan procedure may still be able to have ventricular septation to improve their blood-oxygen saturations.

How we care for double inlet ventricle

Our Cardiac Surgery team achieves some of the best outcomes in the world, but we’re also known for our compassionate, family-centered approach to care. We will provide your family with the information, resources, and support you will need before, during, and after your child’s treatment.